100 years of MPA, 100 years of Transatlantic Cooperation (5)

A Very Old Nemesis: The Early Days of Film Piracy

“I know changing can be scary, but it’s a part of growing up. It’s how we find out who we are and who we’re gonna be.” – Miley Cyrus as Miley Stewart, in: Hannah Montana

Protecting the people who make film and television against the threat of piracy is a central mission of the MPA in 2022. Central, but not new. In fact, the challenge of piracy is even older than our century-old association – as old as moving pictures themselves.

At the MPA roundtable discussion at this year’s Marché du Film at the Festival de Cannes, Paramount Senior Vice-President Andrea Kalas recalled that one of the early “working groups” set up after the MPA was founded in 1922 focused on the need to protect content around the world.

By that time, the destructive power of piracy was already well understood in the industry.

Its most common form was unauthorized “duping” of film negatives, which involved creating new master from used projection prints.

Among the most famous early victims was French illusionist Georges Méliès, who inspired the 2011 movie Hugo and the Méliès Museum at the French Cinematheque in Paris.

Méliès was among the first artists to truly understand the power of the new medium and to create the first special effects. His 1902 film A Trip to the Moon was wildly popular in his home country, which led to widespread copying of his work. Méliès lost out on much of the revenue he deserved, and ultimately gave up on filmmaking.

In the United States, the early history of film copyright was shaped by a 1903 dispute between inventor Thomas Edison and film producer Siegmund Lubin. A blog post from the National Archives recounts that: “At the time, duping other companies’ films and selling them was an integral part of the motion picture business. Lubin did it. The Biograph Company did it. Even Edison’s film production company did it.”

By 1912, the Townsend Amendment to the Copyright Act of 1909 went into effect, officially recognizing motion pictures as eligible for copyright protection as such (rather than as a collection of photographs – the approach pioneered by Edison).

As the early industry expanded internationally, a Variety article in 1914 reported that continued duping of film negatives was “hitting the market a solar plexus” but reassured readers that “it now looks as though every energy will be bent toward protecting copyrighted films and stopping the ‘pirates’ not only in Europe but in America.

Stopping the pirates proved to be difficult. By 1924, the trade publication Exhibitors Herald confirmed that the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA, widely known as the “Hays Office” for its founder Will Hays) was asking governments to take action.

In 1925, a committee drafting the mandate for the MPPDA’s first European representative called for that person “to be particularly on the look-out for pirated prints of American pictures and make every effort to recover such prints or enjoin their exhibition.”

No one could have known then how the problem of making pirated “pictures” available to the public would persist and grow with technological developments, and how the MPA’s antipiracy mission would have to adapt and grow with it.

But everyone knew, from experiences like that of Georges Méliès, that fighting piracy was integral to the mission of creating jobs and growth in a legitimate industry.

Today, in the framework of the Alliance for Creativity and Entertainment (ACE), the MPA is still being recognized for working with a network of partners around the globe to protect the rights of creators and their business partners.

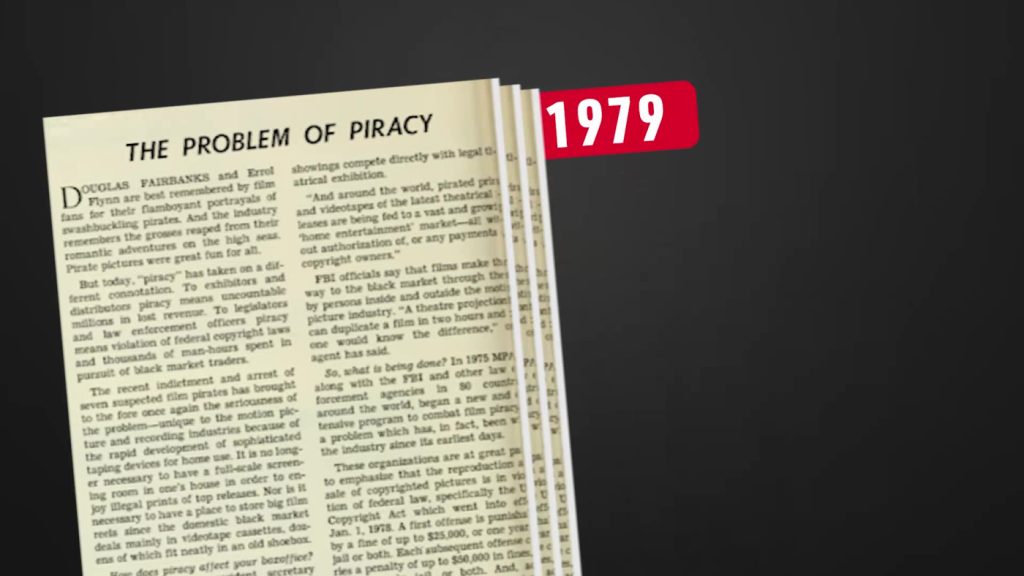

Courtesy of Box Office magazine, first shown at the MPA event entitled “Celebrating 100 Years of Transatlantic Storytelling” at Cannes Film Festival 2022.